What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Utah, where four talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people from various walks of life—whether they are Indigenous, native born, a naturalized citizen, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an American.

Illustration by Yunyi Dai

Standing on ancestors’ shoulders: Passing down what it means to be American and Navajo

Heather Tanana said that the first thing her children will tell you is that they are Navajo. They know their heritage and are proud of it, she said.

That pride in their heritage is reflected in their names.

The oldest is named Soryn Iina and she’s 10 years old. The first name reflects Tanana’s European heritage from her mother’s side. While the middle name means ‘life’ in Navajo, which comes from Tanana’s father’s side.

Tanana’s youngest is Reinhold, a 4-year-old blonde-haired boy full of energy. His middle name is ‘Haskeltsie,’ which Tanana said is a family name.

“Something that I’ve strived to teach them … is that they are also Navajo,” Tanana said, adding that as her kids grow up, she wants them to know about their unique Navajo history.

Tanana said that she learned to be proud of both her Navajo and American heritage because she knows about all of the struggles that Native people endured throughout history.

'We have a real unique history'

Heather Tanana stands in the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law where she works as a research professor. Tanana is also an associate faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health. (Courtesy of Heather Tanana)

Albert Smith (left) and George Smith (right), at a family gathering and sitting next to George’s daughter, Julie Livingston (middle). Albert and George are Heather Tanana’s uncles and were Navajo code talkers during World War II. (Courtesy of Heather Tanana)

A clip from my conversation with Heather Tanana about how her uncles, who volunteered to served as Navajo code talkers in WWII, shaped her American identity. Full story coming out on Friday for #NPRNextGenRadio pic.twitter.com/tylHwZqJHq

— Martha Harris (@marthajharris) August 4, 2021

“There’s a lot of ancestors whose shoulders … we stand on,” she said. “Native people, we do contribute to the United States, we are not this race that disappeared when Columbus came.”

Two of Tanana’s uncles, George and Albert Smith, volunteered to serve as Navajo code talkers during World War II. Along with members of other Native American tribes, her uncles would speak in their tribal language over the radio so that German or Japanese soldiers would not decipher what was said.

“If you think about the time of World War II, Native Americans weren’t guaranteed the right to vote in every state across the United States,” she said.

Yet, her uncles volunteered to fight in the war for the United States

Tanana said that both of her uncles were proud of their service as code talkers. Tanana said that her uncles’ example taught her that you can be an American and still be critical of the injustices that exist across the United States.

“I think being American doesn’t mean being blind to what’s happening in the country,” she said. “It means trying to always strive for improvement, and making a difference, and lifting up everyone across the United States.”

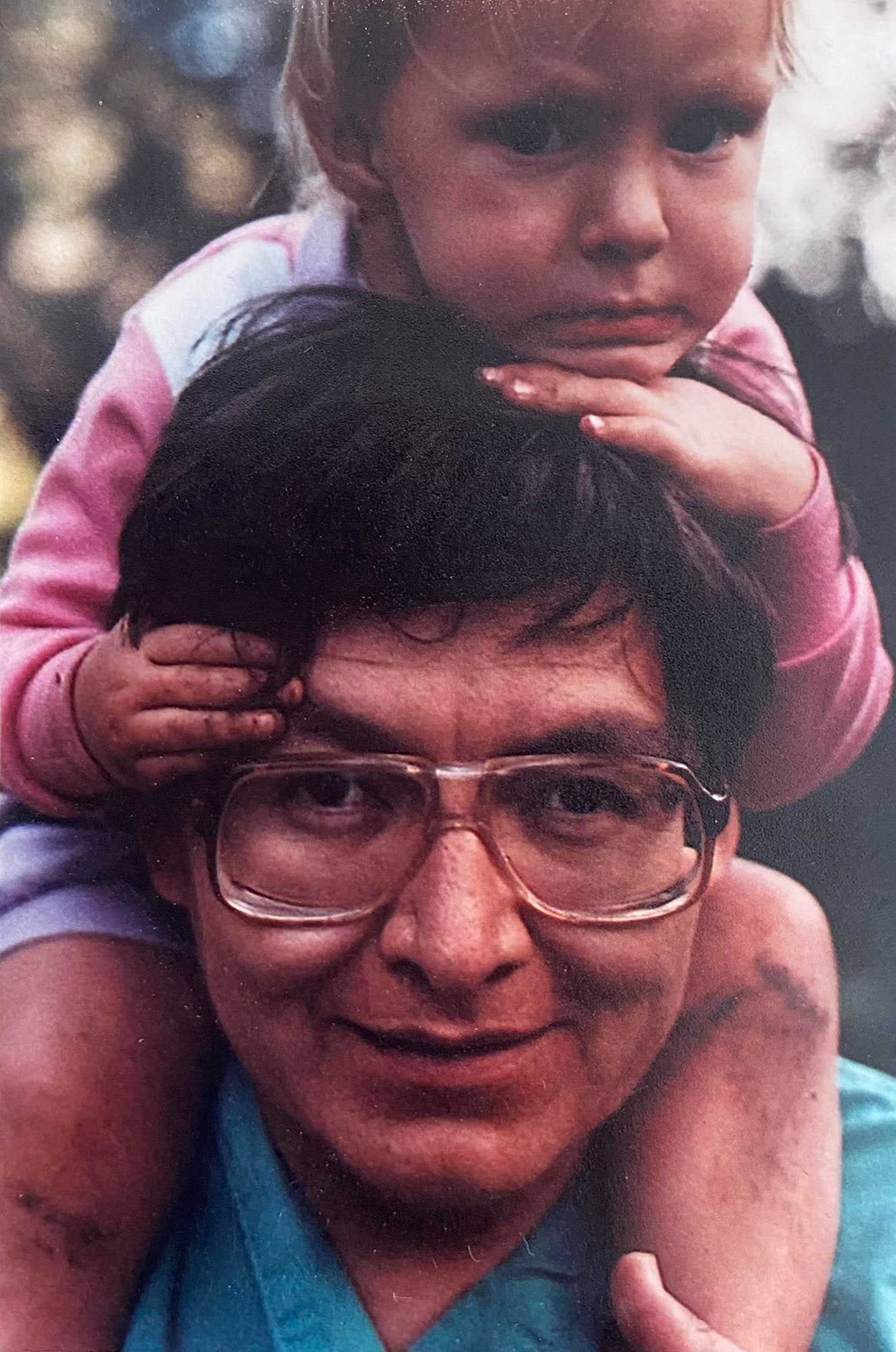

Tanana said that her father, Dr. Phil Smith, has also played a big role in shaping her Navajo and American identity.

“I don’t think I’ve ever felt shameful of my identity,” she said. “If you were to ask my dad, he might answer differently. He was removed from his home and sent to a boarding school when he was very young.”

Starting in the late 1800s and ending in the 1970s , hundreds of thousands of Native American children were taken from their homes and forced to attend boarding schools that were either run by churches or the federal government, according to The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

While at the boarding school, Tanana said her dad was punished for speaking the Navajo language and forced to cut his hair. Tanana said that he was told to adopt the “white man’s ways” in order to be successful.

The founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Richard Henry Pratt, said that the purpose of the school was to “kill the Indian, save the man.”

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced in June the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which will investigate the boarding schools that operated in the U.S. The announcement came after the remains of 215 Indigenous children were found on the grounds of a former boarding school in Canada.

But despite his experiences at the boarding school, Tanana said that her dad is proud of his Navajo identity. Tanana said that it is easier for her today to be proud of her heritage knowing what her dad went through and how hard he had to fight for his identity. She also admires her dad’s dedication to bettering his community.

“My dad dedicated his entire career to the health care of Native American people in this country,” she said. “He worked for Indian Health Service, and that was his way of contributing, recognizing that there were shortfalls in the government and the past way that they had been providing health care, and he personally wanted to make it better.”

Her dad saw a lot of these problems recently during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tanana said that Indian Health Service is underfunded and that the Navajo Nation was hit hard by COVID-19.

“I think there were just a couple of respirators across the entire Navajo Nation, which is roughly the size of West Virginia,” she said.

According to Forbes, the Navajo Nation had the most COVID-19 cases per capita in the U.S. in May 2020. Almost 1,400 Navajo Nation residents have died from COVID-19, according to the Navajo Department of Health. A majority of those deaths were among older adults.

Her father’s career in medicine inspired Tanana to pursue a career in law.

“If you want to make improvements in tribal communities, a lot of times you are having to look at a legal mechanism to do so because there is this government-to-government relationship that exists between tribes and the federal government,” she said. “Which is part of the reason why I went to law school.”

Heather Tanana, at age 2, sits on her father Dr. Phil Smith’s shoulders. When she was younger, they lived in Tuba City, AZ on the Navajo Nation reservation. Tanana was born in Montezuma Creek, also on the Navajo reservation. (Courtesy of Heather Tanana)

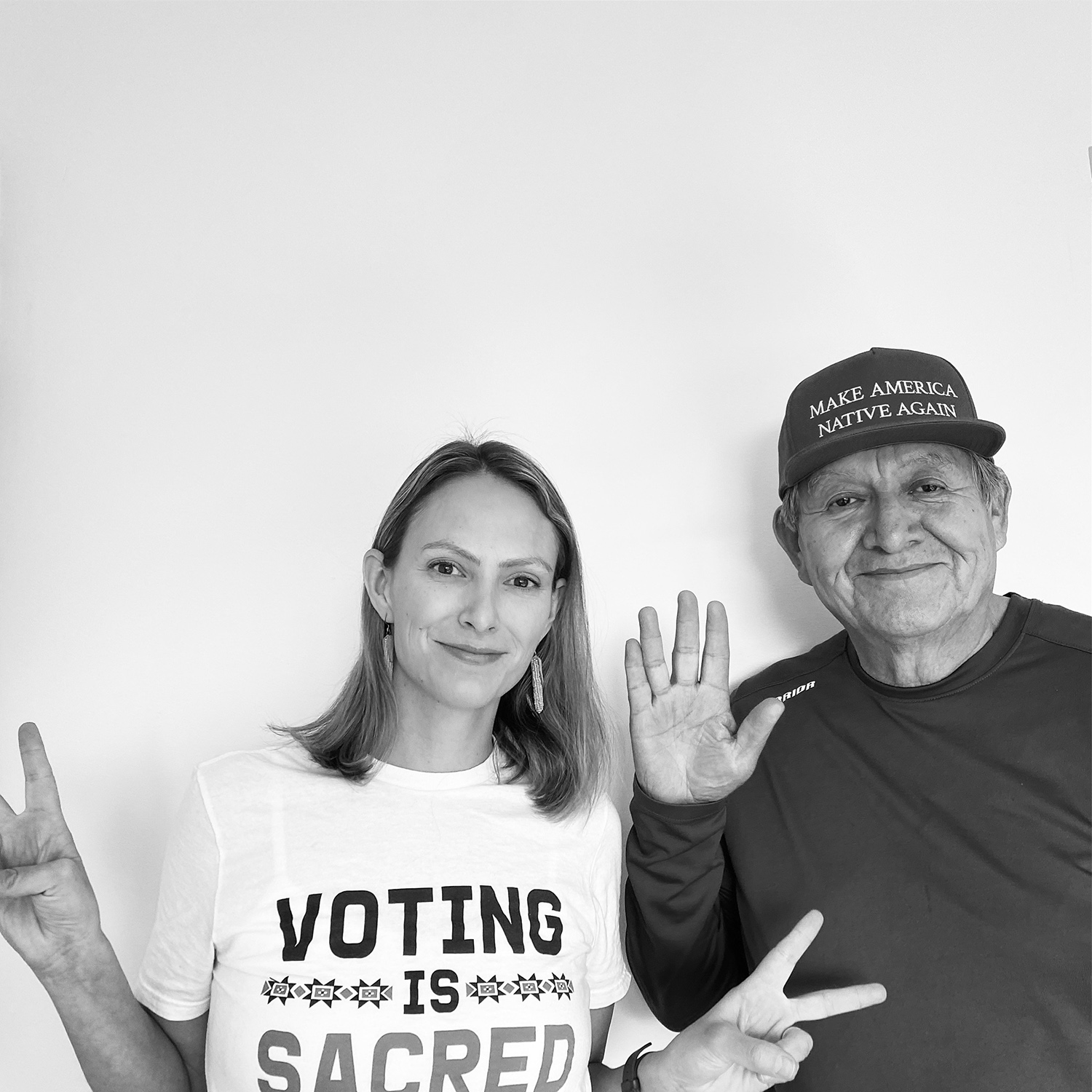

Heather Tanana (left) and her father, Dr. Phil Smith (right), pose for a photo. Smith spent his career working for tribal health clinics and Indian Health Services. (Courtesy of Heather Tanana)

Tanana said that the lessons she learned from her family members have taught her that part of being a good American is recognizing problems in the U.S., and using your skills and time to make things better.

She hopes to pass these lessons down to her kids.

“I want them to, yes, be proud of who they are, but then utilize their strengths to help lift their community so that you can pass it on to the next person, they can accomplish more and build off of your work,” she said.

Heather Tanana and her kids, Soryn Iina Tanana and Reinhold Haskeltsie Tanana, enjoy Monument Valley, UT. Tanana’s kids have European first names and Navajo middle names. (Courtesy of Heather Tanana)